The Lumpen – Free Bobby Now

The Original Last Poets – Die Nigga

Amiri Baraka – Who Will Survive America?

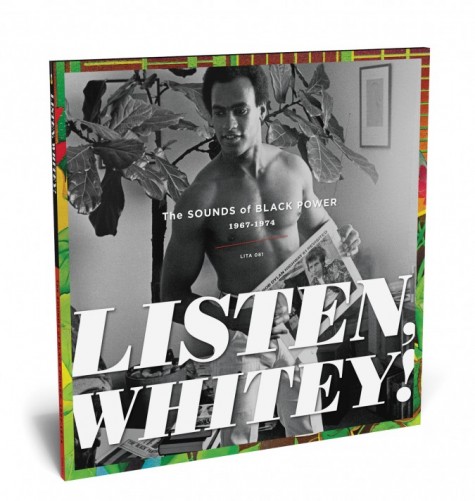

I really can’t explain why this review hasn’t gone up sooner. I’d gotten the collection a full month before it was released, and I don’t like to post about music until it’s actually available for people to get. Planned on reviewing it in February, then was absolutely going to do it in April when I interviewed Pat Thomas, who put together this volume and the book that is it’s companion, but still couldn’t bring myself to post a review. Literally this week I’d thought about doing the post on July 4th, but then couldn’t find the time to write it. However, after the bit of controversy that popped up after Chris Rock’s July 4th tweet, I thought perhaps it’s finally time to write a full review of this collection. Something about the response to that tweet seemed to connect to many of the reasons why I feel like compilations like this are so important, perhaps precisely because of the general collective amnesia so much of the US populace has when it comes to history, something that is particularly on display on the 4th of July.

Listen Whitey!: The Sounds of Black Power 1967-1974 chronicles a very specific period of US history and very specific style of music, even though it includes a variety of genres. All of the songs are directly or indirectly connected to the Black Power movement in the US. In contrast to Civil Rights, Black Power was a much more strident, more militant movement, focused on increasing the self-determination of African-americans in the US. A quick point is to made on the concept of Black Power, because the notion remains controversial 45+ years later (in fact every time I’ve played a track from this collection, I get one upset listener for every ecstatic listener). The fundamental difference between “Black Power” and “White Power” in the US is around the issue of how power is used. “Black Power” is about dismantling undue privileges because of race and class, “White Power” is about denying privileges to others to maintain privilege for a particular group. In some respects “Black Power” seems like an antiquated concept, for many especially so in the age of Obama. But what has become clear (and what many of the responses to Chris Rock’s tweet seem to reinforce) is that issues of race haven’t gone away and issues of racial privilege remain important in contemporary America. That’s part of what makes collections like this so important because they remind us of a history that is not so distant, and one that remains relevant in 2012.

What is truly exceptional about Listen Whitey is the diversity of music and spoken word associated with the Black Power movement that it chronicles. Thomas makes the correct move in highlighting music that was directly associated with the movement as well as music that was clearly inspired by the movement. In terms of “movement music” I was most excited to finally hear music from the Black Panther Party’s musical group, The Lumpen. I’d first heard about them from Brian Ward’s Just My Soul Responding, a book that directly influenced me to take the academic path I’ve taken. All the time I lived in the Bay Area I was on the lookout for this band’s single, but never was able to track it down. “Free Bobby Now” is an upbeat groover that superficially is not that different from a number of soul group sounds from 1970, the difference is all in the lyrics, a call for justice written while Bobby Seale was jailed during the Chicago 8 conspiracy hearings. Even students of this period of time might not have known about this group (though their story will be told soon, by Dr. Rickey Vincent in his upcoming book “Party Music”) and making this music available fills a major gap. Other tracks connected directly to the movement and organizations include Elaine Brown’s “Until We’re Free” (from an album that I believe Huey P. Newton himself writes the liner notes), Shahid Quartet’s “Invitation to Black Power” and spoken word tracks by Stoklely Carmichael and Eldridge Cleaver.

Thomas could have likely included more “movement music,” but instead the rest of the collection is filled with songs inspired by the movement or clearly inline with it’s sentiments. One such track, and another song that hasn’t been issued since first appearing on vinyl, is Bob Dylan’s “George Jackson,” written in tribute to Soledad Brother George Jackson after his assassination in jail in 1971 (which directly led to the Attica prison uprisings later that year). While the full band version has turned up a few times, this acoustic version had been out of print since Dylan strong-armed Columbia to release the 45 with the same song on both sides so people wouldn’t be able to escape his message. “George Jackson” in its acoustic version ranks up with some of Dylan’s best social commentary, haunting, heartfelt and honest, especially in his final assessment of our society, that still rings true, “Sometimes I think this whole world is one great prison yard, some of us are prisoners, the rest of us are guards.”

Another of the highlights of this collection is the Original Last Poets “Die Nigga,” which features David Nelson’s startling, fiery and insightful critique of the way black people have been treated, how they are talked about, how they are valued (or the lack of value attached to them) and how their survival requires the death of all that’s come before. This similar sentiment of rebirth through death is a major theme in Amiri Baraka’s “Who Will Survive America,” the song begins by matter of fact stating that “very few negros and no crackers at all” will survive America. Baraka’s words from there are more directed on critiquing aspects of black culture in addition to the broader American culture before he arrives at the conclusion that black man and black woman will survive. The distinction being made on these tracks and on others is an important one, and one that often gets lost in racial discussions in this country. Simply being a part of a group is less important than how you represent that group. In many instances people within a group, those most resistant or fearful of change, can be a larger problem than anyone who is outside of that group. For America to survive, for us to truly live up to our ideals, we need to be able to recognize hard truths, fully come to grips with our history and its consequences and create something that benefits everyone, only that will allow us to “all survive” as Baraka intones as his closing message. It’s a message that I attempt to impart in my teaching and one that in musical form is at the heart of this collection. Though it is focused on a very particular moment, with music that was designed for a very particular movement, it speaks to issues and concerns far beyond that moment or movement and includes lessons that we all need to be taught and all can learn from.